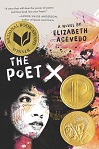

Where fists cease to fight, words take over. In The Poet X, a young girl slams her way into her friends’ and the reader’s hearts with her poetry. Her strong voice not only conveys her stance towards religion and love but also proves the importance of poetry for today’s youth culture.

by Emily Linnéa Lüter

The verse novel has made its way into the 21st century and has taken on the new shape of slam poetry. Elizabeth Acevedo’s debut The Poet X successfully translates a powerful story into a coherent collection of poems which leads the reader through the life of Xiomara Batista, a Dominican girl trying to find her own voice through verse. Being a slam poet herself, Acevedo shows poignantly how this lyrical form is capable of conveying the complexity of a young woman’s spectrum of feelings.

The Poet XXiomara bears the burden of an unusual name: it means ›one who is ready for war‹. Born a fighter, she initially continues to battle with fists. Hers is not an easy life. Though being of Dominican origin, she is Harlem born and

Xiomara’s style is characterised by free verse. Neither rhymes nor metric continuity weave a golden thread through the poems. She writes as she speaks: plainly. Her verses sound more authentic because of it, for just as she refuses to squeeze herself into the shape culture has created for girls, neither does she form her words according to traditional patterns. The frequent use of enjambments generates a dynamic that makes the poems sound lively and more akin to the common use of language. Xiomara’s moods and feelings are reflected in the length of verses and whenever she is overflowing with feelings so do the words filling a line. Analogously, frustration and sadness show in clipped lines.

»When your Body Takes up More Room than your Voice«A girl showing ample skin to provide men with a space to project their lust onto is called a Cuero. Called so by her own parents, mind you. What men say and do determines this girl’s essence. Cat-calling is not seen as an inappropriate imposition on women but as a lamentable state of ›these kinds of women‹. Surely she must have Cuero airs to attract such attention. Xiomara puts the injustice of this label into concise words:

When your body takes up more room than your voice

you are always the target of well-aimed rumours.

In her world the misogynists do not necessarily have male bodies. Xiomara’s own mother is her greatest critic. The allegedly sinful character of the girl she has raised to be sinless brings shame to her house. If only she would listen to what her daughter has to say, who is putting herself into the tradition of women abused by men’s behaviour:

If Medusa

was Dominican and had a daughter, she might

wonder at this curse. At how her blood

is always becoming some fake hero’s mission.

Something to be slayed, conquered.

Contrary to her mother’s firm belief, Xiomara is not a girl who wants to be conquered but who wants to conquer the world – a world in which her body belongs to no one but herself.

Growing up and into a new body and mind at the threshold of adolescence, Xiomara replaces Bible verses with verses of poetry. She knows full well that to her mother her words would seem like pure blasphemy; satanic words flowing through her daughter’s now sullied mind. She fails to recognise how the verses she herself recites to cleanse her daughter are like knives cutting through Xiomara’s heart:

My mouth cannot be shaped into the apology

you say both you and God deserve.

And you want to make it seem

it’s my mouth’s entire fault.

Because it was hungry,

And silent, but what about your mouth?

Mrs. Battista puts her down in the name of God, time and again until it is no longer bearable. Xiomara’s every action is shadowed by the knowledge of how her mother would react if she knew about it: going to a poetry slam contest is out of the question. Is it, really? With the support of her English teacher, her best friend Caridad, her boyfriend Aman, her twin brother and Father Sean she might be able to rise higher in her ambitions of becoming a slam poet than she would ever have thought. The latter’s support is a redemption for the church that she has learned to hate. Ultimately, Father Sean turns out to be the mediator between Xiomara and her mother. Being religious is not as black-and-white a matter as it appears.

Slam poetry, at its heart, is not supposed to be perceived in the written medium. Its true power only unfolds if spoken by the person who created the verses. Acevedo’s live performances breathe life into her words, in gestures and intonation. An audio version of this special novel would therefore be more rewarding. It might lend Xiomara an even stronger voice. And read how strong that voice already is:

And as she [her mother] recites Scripture

words tumble out of my mouth too,

all of the poems and stanzas I’ve memorized spill out,

getting louder and louder, all out of order,

until I’m yelling at the top of my lungs,

heaving the words like weapons from my chest;

they’re the only thing I can fight back with.