Content warning: mentioning of trans*phobia, suicide

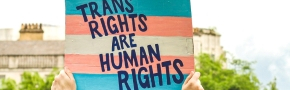

What does it mean to become a white man in the US in 2017? What does it mean to be trans* in contemporary America? Trans* author P. Carl traces the fine line between privilege and discrimination. On Wednesday, 14 November, he read from his upcoming memoir at Göttingen University.

By Hanna-Maria Vester

In his memoir Becoming a White Man, P. Carl relates the public and private consequences of his transition. Though very comfortable with his gender, Carl insists he cannot ignore the uncomfortable political implications it entails. On 14 November, at the invitation of the North American Studies Department and the Göttingen Centre for Gender Studies, he made his way to Göttingen. This, for him, is an »exciting and nerve-wrecking time«. He is currently waiting to hear if his editor likes his book as much as he and his agent do, as he puts it. At the same time, Carl admits, it is very hard to share such a personal book with the public.

Before he begins to read on this rather dark Wednesday afternoon at the University of Göttingen, Carl positions himself. A desk between him and his audience. Standing behind it, he explains, half-jokingly, half in earnest, that this is typical of people who have written a memoir. He is trying to keep a safe distance in a moment of vulnerability. But this non-fiction writer, lecturer and dramaturg turns out to be anything but removed from his audience, let alone his subject matter. His book is all about making sense of the diversity of experience, of tracing the distance between people in the hope of overcoming it. Theatre-man that he is, he reads from his upcoming book with ease and un-staged sincerity. A multi-faceted monologue, which transcends the physical realm and unfolds in the minds of his audience. The table in between, as it were, does not ›matter‹.

À La Beauvoir: Becoming a Man

In the first chapter of his book, P. Carl sets the scene: it is on 16 March 2017 in the Chandler Hotel in Manhattan that he joins a reality-defining club. Upon turning 51, »I am finally me«. This is the moment of revelation, a feeling of intense newness. Carl lived as a masculine woman before his transition, studying men’s mannerisms, fashions and roles. He began Testosterone Therapy in 2017. Carl describes transitioning as his body catching up with his mind – finally they are in sync. He relates the difficulty of explaining this and offers approximations: »It wasn’t something I knew I wanted, something I chose. It was a longing«. He knew and simultaneously, he didn’t know. And yet, »My body thought people knew I was a man. Is this what dysphoria feels like?« If this sounds paradox, that’s intentional and true to Carl’s experience. »I love this body and all its contradictions. I am a work in progress.«

P. Carl

Event Series

GCGS

Their lecture series in collaboration with the department of Comparative Literary Studies Gender Stories deals with themes and theories of literary gender studies and takes place every Monday from 6.15pm, in ZHG 101.

Let’s Get Physical: A Man, Not a Construct

How can a combination of body parts lead to depression, even the contemplation of suicide? How, in turn, can it create profound happiness? Carl describes how he enjoys the comforts of being a man. Before and after his transition he indulges in gendered consumerism. The world, he notes, is intensely gendered, and he happens to feel at home in spaces coded as male. He engages in the infamous locker room talk, in both empty banter and meaningful discussions with men. It is, however, especially the physicality of being a man which is important to him. Being a cultural studies scholar himself, he found it difficult to come to terms with that reality: Does that mean he fails as a feminist? In contemporary Gender Studies and the majority of feminist activism, the focus certainly seems to lie on gender as a construct. Carl’s experience, however, questions this emphasis. There lies a deeper knowledge in corporeality, Carl claims, and advocates that there is still a lot of work to be done in the study of the body and gender, and the language that we use to describe it.

Bodies do matter. And here we are, that’s the dilemma of the social constructivist. The reduction to hormones is exactly what feminists criticise, you may rightly say – and so did an audience member. Carl agreed. The strength in his argument lies therein: Carl recognises and addresses the potentially essentialising discourses surrounding trans*gender identity and offers approaches to counteract them. And similarly, his experience of gender does not deny non-binary genders. He argues that there is a lot yet to learn about non-binary genders as well, that they are an important facet of gender. »If we had progressed further as a society and non-binary genders were more accepted, I think it would be easier for you to sit back and enjoy your masculinity«, another listener notes. Since feminism has never been a container for fixed, easy concepts, his writing promises to be a valuable contribution to inclusive feminist activism in all its complexity.

Let’s Get Personal: Trans*phobia and Sexism

Carl’s transition did not only challenge his intellectual understanding of gender, but also his personal and professional relationships. An inversion occurs: Before transitioning, Carl was very much accepted as a queer woman by his friends, contrary to the experiences he had outside of this private realm. After his transition, he is more accepted as a white male in public spaces – but his private life is shaken up considerably. In how far do our body parts negotiate our relationships with other people? What qualities of sex and gender make a friendship? Mourning did not occur to him when he transitioned. But it did to others. He had once promised his girlfriend, now wife, that he would not take Testosterone. And he broke that promise to a woman who firmly identifies as a lesbian. Some friends felt betrayed, Carl’s body »threatening the chronology of history and memory of others«, his »quirky, queer, androgynous body« now unexpectedly re-inscribed as a male body. A certainly very difficult, intimate and complex aspect of this is also his relationship to his parents to which Carl dedicates an entire chapter.

›Polly Carl‹ becomes ›P. Carl‹ in 2017. The ›P.‹ expresses the continuity between the two people he has been. He chooses ›Carl‹, his former last name, because “I recognise he has always been with me”. Importantly, he acknowledges the difficulty that is sometimes attached to referencing a previous name in the trans* community1. Yet, allowing both Carl and Polly into his writing enables him to compare and contrast, to alternate between ›his‹ and ›her‹ experience: »Polly’s memory in Carl’s body.« This makes it easier to recount and bring to paper all the harassment and gaslighting, he says. It is only now that he has the necessary distance to understand the actual scale of the sexism he experienced. He cannot unknow »what men do to women«.

Becoming a White Man

Carl is definitely at risk for being trans*. And yet, he is also privileged as a white male. In Becoming A White Man, Carl writes about the change from being perceived as a middle-aged queer woman to being seen as a white man »in the year that white male bodies represent everything that is wrong with America«. Political structures are drenched in patriarchy and white supremacy, with one white (if slightly orange-y) man setting the dominant, unequivocally hostile tone. P. Carl becomes a white man in the wake of the #MeToo-movement, in a time when US media and the constant murders of black bodies by white hands seem to say ›black lives don’t matter‹. It is a time when trans* people’s existence remains constantly threatened – whether by laws that deny trans* rights and trans* existence, or by the rise in the murder of trans* women. The anxiety around white masculinity rises to peak levels and endangers democracy’s core values, not just in the US. And P. Carl comfortably, happily settles with becoming a white man? Far from ignorant of the present climate, he reconsiders himself in relation to it.

Carl realises the power he has. He has inhabited two bodies, as he puts it, and he has insights from two very different experiences. In that he sees his purpose to offer a complex view in a time when complexity is wilfully ignored in favour of simplistic divisions between ›us‹ and ›them‹. This is what he needs to explore, he explains: »I can’t just enjoy myself: I have to double2, I have to tell my story«. His book is testimony to both his comfort and his discomfort. As Hannah Gadsby, an important voice in relation to gender non-conformity and LGBTQ* activism, put it in her recent Netflix stand-up special Nanette: »stories hold our cure«. Carl’s memoir might not give all the answers or provide a simple antidote to hate and discrimination. But art, he says, can convey the nuances and intricacies of identity and lived experience. It is the necessary vehicle to understand each other’s different bodily realities, in a time when so many bodies, be they black, female, trans*, non-binary or immigrant bodies, are under attack. P. Carl’s upcoming book promises to be such a piece of art. While his writing is undoubtedly political, it is his poetic style that allows him to encapsulate his experience so effectively, beautifully and empathetically.

- »For some trans*gender people, being associated with their birth name is a tremendous source of anxiety, or it is simply a part of their life they wish to leave behind. Respect the name a trans*gender person is currently using. If you happen to know the name someone was given at birth but no longer uses, don’t share it without the person’s explicit permission.« (More useful information can be found here). ↩

- Carl refers to ›doubling‹ in reference to W.E.B. du Bois’ concept of double consciousness, but possibly also to the practice of doubling in theatre, during which one actor plays two roles in one play. ↩